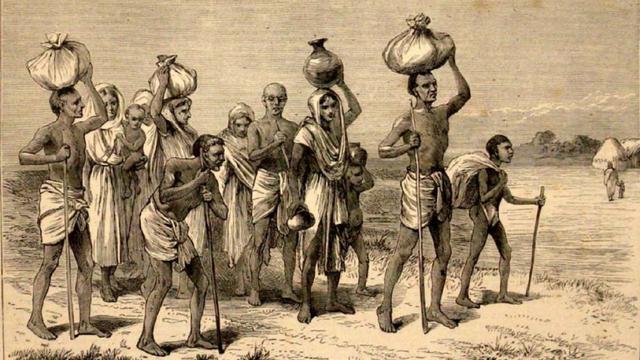

The sudden rise of land revenue taxes, together with drought, caused what some now call a genocide, which killed from one to ten million Bengalis and Biharis.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Introduction to the webinar “Social Justice, Tax Reform, and the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on February 20, 2023, World Day of Social Justice.

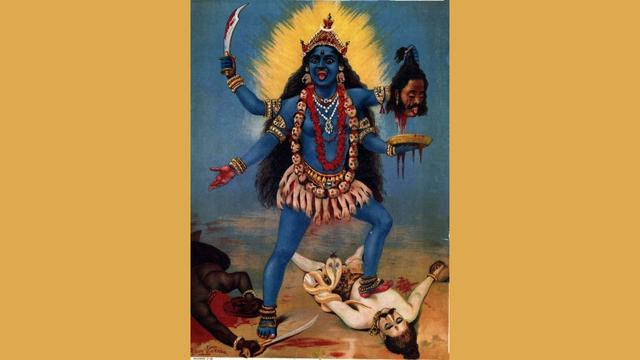

According to a tradition that may or may not be true, in 1775 one of the greatest Indian mystics and poets of that century, Ramprasad Sen, entered River Gange singing the praise of Goddess Kali. He continued to advance into the river until he died. Although common onlookers believed he had drowned in the river, according to his followers he had entered into an embrace of pure bliss with the Goddess, and had died in that beatitude.

This real or imaginary death—others believe Ramprasad died of old age and illness some twenty years later—marked the zenith of a religious revival in Bengal, which made the devotion to Goddess Kali and Tantric rituals inspired by her immensely popular in Eastern India. Religious historians know that often revivals happen after a deep social crisis. The Kali revival in Bengal was no exception. It came after one of the worst disasters in Indian history.

East India Company was a British private company that came to rule most of India in the century between 1757 and 1858, when control of the country was transferred to the British government. In 1764, after a victorious military expedition, the Company obtained administrative control of Bengal (which at that time also included present-day Bangladesh and parts of Bihar and other Indian states) and the right to levy taxes there. The Company realized that the most profitable way of taxing Bengal was by collecting land revenue taxes, whose basis was easy to ascertain, through local tax collectors, who were encouraged to be effective by a system of percentages and bonuses.

Land revenue taxes existed in Bengal before 1764, but the Company suddenly raised them by 30% and imposed a yearly quota tax collectors should reach—no matter how. This placed an impossible burden on impoverished Bengalis, and combined with droughts in 1768 and a smallpox epidemic, made it impossible for most of the population to pay. Tax collectors, however, did not want to renounce their bonuses, and used violence to compel the taxpayers to pay. In 1769, the rain fell again, which would have improved the situation, but the collectors had to meet their quotas and further increased their tax requests, making once again payments impossible.

The result was that most Bengalis and Biharis, after having been forced to pay the taxes at gunpoint, had no money left to survive. The original estimate of the victims of what was called the Great Bengal Famine was ten million. Some modern historians have revised it to one to two millions, but nobody really knows because counting the victims in rural areas was impossible.

Most died in 1770, when both the smallpox epidemic and the drought had, at least temporarily, subsided, proving that the root cause of what today many call a genocide was the taxes. If it was a genocide, it was a human-made one, and perhaps the only genocide in history caused by taxes.

I have mentioned the Kali revival that followed, which also reaffirmed a religious identity Bengalis had perceived as threatened and denied by the East India Company. The terrifying iconography of the Goddess Kali became a fiery symbol of anti-British Indian resistance, well into the 20th century. Kali had become the Goddess of Indian independence, justice—and protest against disastrous taxation.

This connection between spirituality, justice, and tax reform has not lost its relevance today. Happily, we do not see tax genocides in our time, but tax injustice can still create considerable suffering. The Tai Ji Men case is an egregious example of how taxes can be used to create great social injustice and to persecute spiritual movements.

It is something fit to remember on the World Day of Social Justice, and after the proposal by the Shifu (Grand Master) of Tai Ji Men, Dr. Hong Tao-Tze, in cooperation with the Association of World Citizens, to designate December 19, the day the Tai Ji Men case started in 1996, as the “International Day Against Judicial and Tax Persecution by State Power.”

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770 reminds us that taxes have a destructive power, and may be used to deny freedom of religion or belief as well. This is why we support Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) in their protest—and support the “Declaration of the International Day Against Judicial and Tax Persecution by State Power” as well.

Source: Bitter Winter