Caring for the others is not just sharing material interests but recognizing the value of all human beings. This is what Tai Ji Men teaches.

by Marco Respinti*

*A paper presented at the seminar “Global Solidarity with Tai Ji Men: 26th Anniversary of the Raid Which Began the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized on December 19, 2022, on the eve of International Human Solidarity Day, in Pasadena, California, by CESNUR, Human Rights Without Frontiers, the Tai Ji Men Qigong Academy, the Association of World Citizens, Action Alliance to Redress 1219, the website TaiJiMenCase.org, and FOREF (Forum for Religious Freedom Europe).

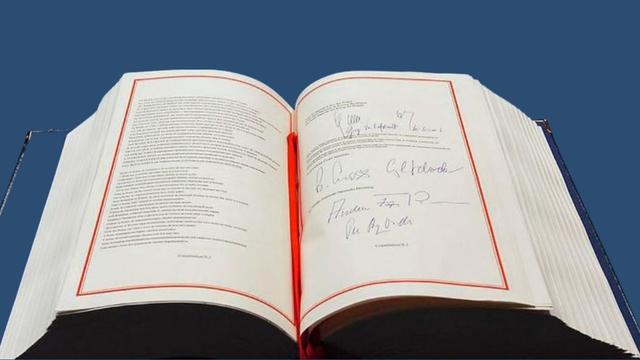

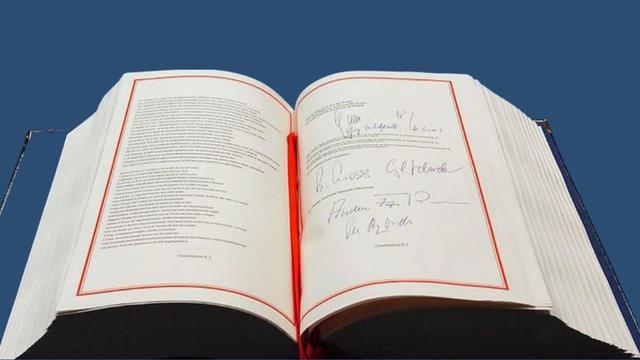

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union was drafted by the European Convention and proclaimed on December 7, 2000, by the European Parliament, the Council of Ministers, and the European Commission. It has full legal status since December 1, 2009, when the Treaty of Lisbon (which forms the constitutional basis of the European Union, or EU) became effective. It is a central document of the EU since it states and upholds political, social, and economic rights that the EU considers to be fundamental for all the citizens of its member-states.

Its Chapter IV is entirely dedicated to solidarity. It addresses some key points: labor and workers’ rights to information, consultation, collective bargaining and action, access to placement services, protection from unjustified dismissal, fair and just working conditions, prohibition of child labor, social security and social assistance, health care, consumer protection, and even protection of the natural environment.

The Charter’s quite extensive and precise prescriptions to ensure solidarity to the EU citizens constitutes the rationale of some of the most important guarantees for European people, yet the Charter cultural value is not for the Europeans only. In fact, beyond its strict legal jurisdiction, the philosophy of the Charter enshrines concepts that are shared by all democratic countries, West and East. To some extent, it represents the goal reached by our civilization in one of the pivotal aspects of public life. In one word, it is an exemplification of what our world means when it speaks of social progress.

Nonetheless, the concept of solidarity addressed in the Charter and its philosophy is quite limited. In that document, solidarity is perceived as the defense of shared interests and objectives in the working place. Basically, it is understood as sympathy based on class. I understand how much this is important, especially at a practical level. But obviously this concept is too narrow.

This kind of solidarity is important for contemporary social philosophy, but it is restricted. Probably not by chance, solidarity is not even mentioned in the European Convention on Human Rights nor in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Yet, solidarity should be addressed in a broader and more profound sense.

Solidarity is not just a commonality of practical aims or sharing of material interest. It is a more profound human value based on a non-negotiable principle: solidarity is in fact the name we give to the sense of unity among human beings that derives from their humanity. Humans beings are supportive and sympathetic between themselves because they understand they share the same nature. They understand they have a common origin and share a common aim. They perceive, in short, to be a lively community, whose destiny is common.

For this reason, they stand together, help one another, are moved by compassion, and practice charity. Solidarity seems to be a word emerging from the jargon forged in the smoky industries of the late 19th century, in the assembly lines where humans counted less than machines, in the coal mines where the life of people, often of young workers, counted for nothing. Maybe this is where the word comes from, but solidarity is much more than that. It is the name we give to a profound spiritual bond that makes humans brothers and sisters.

Solidarity goes in fact far beyond Karl Marx (1818–1883)’s class consciousness, because is not a class concept. True solidarity cuts among classes and sectorial interests to unite different people into a broader sense of community. Through solidarity, people are united not by their own horizontal interests, but their legitimate interests unite them in a common effort to build a humane society. Not envy or greed guide them, but the sense of duty and liberality. From different walks of life, true solidarity brings human beings together instead of organizing them along resentful claims.

One element in Chapter 4 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union seems to go in the direction of a broader and deeper understating of solidarity. It is Article 33 on “Family and Professional Life.” Article 33 consists of two sections. Section 2 states that “to reconcile family and professional life, everyone shall have the right to protection from dismissal for a reason connected with maternity and the right to paid maternity leave and to parental leave following the birth or adoption of a child.” It still insists on solidarity as protection on the working place, but its foundation on Section 1 is the most important aspect of this part of the EU Charter: “The family shall enjoy legal, economic, and social protection.” This section proclaims that the family deserves specifical protection based on the spirit and letter of Article 16, Section 3, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.”

This is of crucial importance, because the family is the cradle of solidarity and the school where we all learn solidarity. The family is the opposite of a union based on class interests. It is not about parents against children, or young against adults. In a family, all members are individuals, yet all are one. They all contribute to a better place for themselves, and healthy families contribute to the general social welfare. They have a commonality of intent to which they contribute, each according to its measure, talent, age, role, the aim being the common good. In a family, members learn from one another: of course, children learn from parents, but also parents learn from children, because no one is born knowing how to be a good parent. Parents learn it while doing it.

We often say that the family is the model of society. It is so because humanity is a great family. The “human family” is a wonderful expression. Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights precisely uses this language, where it says that “the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

Peace in the world is the goal of Tai Ji Men, and Tai Ji Men can be regarded as a family: one large family within the grand human family, made of many families. Each family belonging to Tai Ji Men both teaches other families of Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) and learns from them, as all families do. Families belonging to Tai Ji Men also teach their values to families outside Tai Ji Men and learn from them, as members in all families do. Tai Ji Men as a large family made of many families that are both learning and teaching, in turn teaches its values to the general human family as well, as it learns from it.

What is learned and taught in these families is solidarity, as a spiritual bond based on the sympathy among humans, which in turn is generated by the common human nature of their members and their sharing of the same goal—the good life that only peace can grant.

Tai Ji Men is a great school of solidarity, where care for the others is not just sharing material interests but recognizing the value of each and all human being as unique co-workers in the field of common good. This solidarity cuts across and defeats any divisive logic based on sex, ethnicity, religion, wealth, and class conscience, in a superb contribution toward creating a better place for humanity.

26 years of persecution against Tai Ji Men as of today, December 19, 2022, represent a strong blow against human solidarity. More than a quarter of a century of harassment against Tai Ji Men has persecuted this school of solidarity where people learn to be less selfish. Tai Ji Men is a school where every dizi learns and teaches that human beings are travelers on a boat sailing on perilous waters, but never get lost because they help each other staying afloat, collaborate in navigating, take mutual advise on the best route, fall together to immediately rise up again through the hand of a brother or a sister.

Solidarity is what has given and gives Tai Ji Men Shifu (Grand Master) and dizi the strength to endure in the dark night of unjust persecution. Solidarity is the humble answer that Tai Ji Men has given and gives to the arrogance of arbitrary power. Solidarity is the lesson taught to Tai Ji Men by these hard circumstances. Solidarity is what we can all preciously learn from Tai Ji Men: a brotherhood of fellow human beings called to be normal, daily heroes in our normal, daily lives.

Source: Bitter Winter