Words may be easily used to discriminate against religious or spiritual groups. There are examples even in music.

by Susan Wang-Selfridge*

*An in-session response to the papers presented by Holly Folk, Donald Westbrook and Rosita Šorytė in the session “‘Cults’: The International Return of a Dubious Category,” at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, Los Angeles, August 7, 2022.

Certain words are used to create and perpetuate prejudice. I have studied and taught music all my life, first as a lecturer at the University of California Los Angeles, where I had earned my PhD, and then as a private teacher. Music can teach us something about stereotypes, labels, and prejudices too.

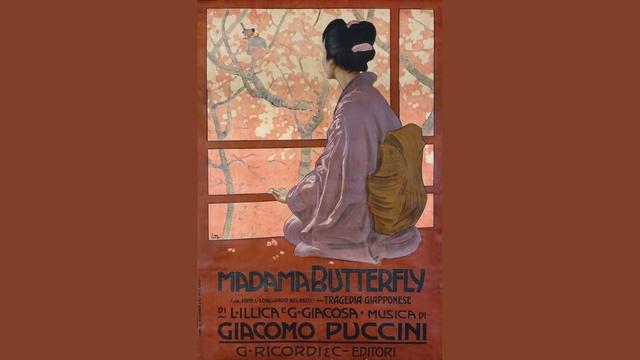

I would mention only one example. “Madama Butterfly” by Italian composer Giacomo Puccini premiered in 1904 and is among the six most performed operas in the world. Yet, recently it has been criticized by some, including in The New York Times, as perpetuating racist and orientalist prejudices.

For those who do not know it, the opera is the story of a Japanese girl from Nagasaki whose name translates as “butterfly.” She marries an American naval officer called Pinkerton. Unbeknownst to Butterfly, Pinkerton regards the marriage as temporary only. The officer then returns to the United States, and does not come back to Japan for three years, although the American consul in Nagasaki has informed him that Butterfly gave birth to his child. Finally, Pinkerton appears in Nagasaki but he does so with his new American wife, who has accepted to raise Butterfly’s child. When Butterfly understands the situation, she commits ritual suicide.

Puccini’s opera has several sources, but the most important one, which already included the names Pinkerton and Butterfly, is a short story, also called “Madame Butterfly,” published by American lawyer John Luther Long in 1898. This detail is important, because Long was an admirer of the feminist movement and his story portrays Pinkerton as a male chauvinist and Butterfly as an abused woman.

Clearly, Puccini’s libretto includes some orientalist prejudices and its depiction of Japanese laws of the time on temporary marriage and divorce is not accurate. However, the audience is led to sympathize with Butterfly and regard Pinkerton as the villain. The American naval officer is a good example of how prejudice works. For him, Butterfly, who has not been raised Christian (although she is prepared to convert to Christianity for the love of Pinkerton) would never be a good Christian wife and mother, and he seeks a Christian woman in the U.S. for a “real” marriage. In this sense, although some passages of the opera may look racist to a 21st century audience, its libretto can also be read as an indictment of Pinkerton’s own racism.

Pinkerton’s prejudices have a strong basis in religion, and Butterfly is depicted as the niece of a Buddhist monk. For the American officer, religions other than Christianity just cannot be taken seriously and respected as one would when confronted with a “normal” Christian denomination.

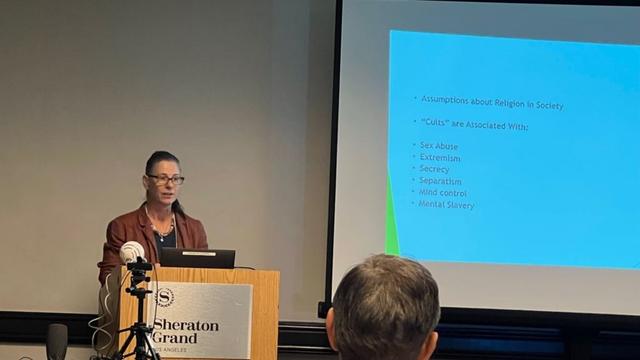

This is very similar to the dynamic at work today around the word “cult.” When political or social groups want to indicate that certain religions cannot be taken seriously and are not respectable, they use the word “cult” to stereotype, malign, and marginalize them.

As Holly Folk has indicated, “cult” has become such a universally recognizable stereotyping word that it is now used also to describe social movements that are not religious. Those who call them “cults” simply want to designate them as dangerous. And dangerous they may well be, but the use of the word “cult” only adds to the confusion.

Donald Westbrook discussed the Church of Scientology, to which he has devoted two important books. From his paper, we see that in this case “cult” as a noun is used, as in other cases, in conjunction with the adjective “secretive.” Westbrook clarified that there is nothing particularly sinister in how Scientology, as many other religions do, keeps some of its teachings secret. He also stated that most critical accounts of Scientology ignore the daily experiences of the “ordinary Scientologists.” Scientology thus becomes a case study of the confusing and discriminatory use of the word “cult” presented by Holly Folk.

Rosita Šorytė introduced some other labels used in Russia: “totalitarian cults,” “destructive cults,” and “extremist religious organizations.” She noted how these labels have been used to ban and “liquidate” peaceful religious organizations such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and to falsely argue that “cults” fueled the anti-Russian sentiment in Ukraine, thus serving as part of the justifications for the Putin regime’s war. This is just another example of how words and labels may play a powerful discriminatory role and even lead to harsh legal measures if not to wars.

Significantly, Holly, Donald and Rosita have all also studied the situation in Taiwan and lectured on the Tai Ji Men case, another egregious example of labeling and discrimination. The Tai Ji Men case also proves that words are used as weapons to unjustly discriminate against spiritual movements.

Source: Bitter Winter