12/09/2021 MASSIMO INTROVIGNE

The label xie jiao has been used in Imperial China, Communist China, and Taiwan to discriminate against spiritual groups perceived as anti-government.

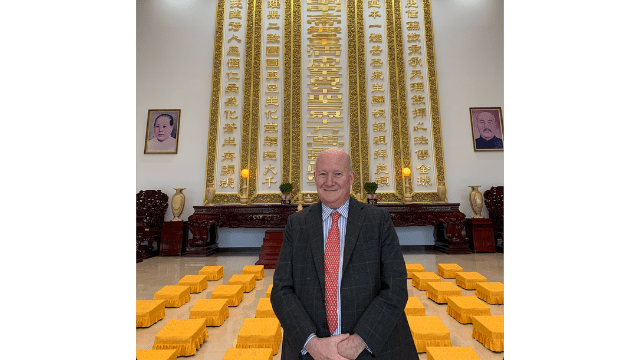

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the mid-term conference of the Research Committee on Sociology of Religion (RC-22) of the International Sociological Association, Vilnius, Lithuania, November 11–14, 2021.

On September 30, 1949, the day before he started his 27-year term as the first Premier of Communist China, Zhou Enlai led the 3,000 delegates of the First Conference of Chinese Political Consultation to Tiananmen Square, where they broke ground for the Monument to the People’s Heroes. After Zhou Enlai, Chairman Mao himself spoke. He described the eight bas-reliefs to be constructed for the monument, honoring eight Chinese revolutions. The second was to celebrate the Jintian Uprising of 1851, when Hong Xiuquan started what will become the Taiping Rebellion.

In the following years, Mao personally ordered to celebrate Hong and the Taiping through monuments, museums, novels, and theatrical plays, soon to be supplemented by television series. This has been continued by all Mao’s successors, including President Xi Jinping.

That Mao and the Chinese Communist Party celebrate Hong contrasts with how the founder of the Taiping movement was seen in Imperial China and by 19th century Western politicians and scholars (including Karl Marx, who unlike Mao had a very negative view of Hong).

Hong proclaimed himself the younger brother of Jesus, married eighty-eight wives, had those of them who displeased him or forgot they should constantly smile beheaded. The war to eradicate the Heavenly Kingdom he managed to establish costed China between 30 and 70 million deaths. Although some Western historians have re-evaluated Hong’s religious creativity, in modern journalistic jargon he would be the quintessential “cult” leader, and in Imperial China the Taiping were considered a stereotypical example of a xie jiao, a word often translated in English as “evil cult” but whose exact meaning is the subject matter of this paper.

Mao, who launched the first great campaign to eradicate the “xie jiao” in Communist China, arresting in the 1950s more than 13 million members of Yiguandao and other religious movements, regarded the Taiping as a patriotic proto-Communist movement. Indeed, calling the Taiping a xie jiao remains forbidden in contemporary Mainland China. For different reasons, considering them good Han Chinese rebelling against the foreign Manchu Qing dynasty, Chinese nationalists from Sun Yat-Sen (who even nicknamed himself “Hong Xiuquan the second”) to Chiang Kai-Shek, also considered the Taiping a legitimate patriotic movement rather than a xie jiao.

The same contrasting judgments have been formulated for the xenophobic and anti-Christian movement of the Boxers, exterminated by the foreign forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance in 1900 and 1901 after it had killed some 30,000 missionaries and Chinese Christians. Last month a controversial book calling the Boxers a xie jiao written by Chinese dissident Liu Qikun and published in Taiwan has been banned in Hong Kong. The new National Security Law has been quoted, and the fact that offending the Boxers, regarded as good patriots, and labeling them a xie jiao is forbidden in Mainland China.

By mentioning these examples, I am not suggesting any conclusion about either the Taiping or the Boxers. My point here is to show that the label xie jiao has a strong political content, something that is important for understanding the anti-xie-jiao campaigns both in Mainland China and in Taiwan.

In 2020, Zhang Xinzhang, a professor at the School of Marxism of Zhejiang University, published an article on the meaning of xie jiao, which he said originated from conversations with the undersigned after he had read some of my articles on the issue and had visited me in Italy. Zhang stated that it is a mistake to translate xie jiao as “cults” or “evil cults.” To him, these translations are misleading. He recommended not to translate xie jiao, and to simply transliterate it, as scholars normally do for qigong or kung fu.

Although the main argument used by Zhang was political, i.e., that the main feature of xie jiao is to be perceived as hostile to the government and dangerous for social stability and harmony, which is not necessarily part of the meaning of the word “cult” in English, I believe that a strong argument in support of his idea not to translate xie jiao comes from history, as evidenced by the studies of Wu Junqing.

Translating xie jiao as “cults” is anachronistic. Jiao means “teachings” and xie means “twisted,” “bent,” and when applied to ideas “incorrect” or “wrong.” This application predates the Christian era. However, the compound xie jiao was first used by an identifiable historical figure, Fu Yi, a Taoist intellectual and Tang courtier who lived from 555 to 639 CE. Fu was persuaded that Buddhism was a mortal threat for China and should be eradicated altogether, if necessary by exterminating Chinese Buddhists. In two texts written in 621 and 624, he explained why this was necessary and Buddhism was a xie jiao, a newly coined term indicating “heterodox teachings.”

Already in the first use of the term by Fu Yi, we may see that theological criticism of Buddhism was secondary. For Fu, the two key features of a xie jiao are not theological. First, a xie jiao does not recognize the absolute authority of the Emperor and does not support the state. Second, xie jiao are expression of a “barbarian wizardry” which is not part of the great Chinese religious tradition. Fu Yi had nothing against magic in general. In fact, he was the Great Astrologer of the Tang court. What he meant is that Buddhism was using black magic.

While, as we all know, Buddhism was finally not eradicated in China, although it was periodically persecuted, the Medieval Song and Yuan dynasties continued to use xie jiao to indicate movements they planned to eliminate, including the elusive “White Lotus,” a group frequently prohibited by Chinese Emperors but which, according to Dutch scholar Barend ter Haar may never have existed as such, with “White Lotus” being a label affixed to different and unrelated movements the state had decided to eradicate for political reasons. The two features of a xie jiao remained being perceived as anti-government and being accused of using black magic, including raising goblins and casting malevolent spells.

It was during the late Ming era that the prohibition of xie jiao, with the death penalty for those involved in its activities, was officially legislated, and movements were officially declared xie jiao first at local and then at national scale. In the 17th century, they included once again the White Lotus, and also Christianity as a whole. Christians were also accused of practicing black magic, including tearing out the eyes and internal organs of children and using them in alchemical rituals.

Later, the case of Christianity continued to prove that listing a religion as a xie jiao or removing it from the corresponding list largely obeyed to political motivations. The Qing listed Christianity as a xie jiao in 1725 but took it off the list in 1842 due to pressures by the Western powers.

Nationalist China, Communist Mainland China, and Taiwan did not invent the category of xie jiao but inherited it from a century-old tradition, which had very little to do with Western controversies about “cults.” I have written extensively about the campaigns against xie jiao in Communist China, and article 300 of the Chinese Criminal Code, which makes it a crime punished with substantial jail penalties “using” a xie jiao, i.e., being active in a group included in the list of the banned movements in any capacity. I would not deal further with the People’s Republic of China today.

Rather, I would like to insist on the fact that fighting xie jiao was not a feature distinguishing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from its nationalist counterpart, the Kuomintang. Certainly the CCP’s struggle against the xie jiao cannot be compared quantitatively to the parallel struggle by the Kuomintang, if we consider the number of those arrested and executed. However, from a theoretical point of view, both Sun Yat-Sen and Chiang Kai-Shek shared with Mao the idea that xie jiao should be eradicated.

Chinese nationalism was born as a progressive ideology of modernization, and xie jiao were seen as “superstitious organizations” (mixin jiguan) resisting modernity and progress. Although as scholars such as David Ownby and David Palmer have noted, nationalist governments in Mainland China were consistently busy with other priorities and never managed to develop the effective anti-xie-jiao apparatus that Mao was able to build since the 1950s, their ideologists continued to call for crackdowns on the xie jiao, and sometimes they were heard. In 1927, for instance, one of the largest new religious movements that existed in China, Tongshanshe, was the victim of one such crackdowns.

Spirit-writing religions, i.e. groups that obtained their sacred texts from spirits through forms of automatic writing, such as Daoyuan and Wushanshe, were also persecuted.

After the Communist victory in China’s Civil War, the Kuomintang establishment moved to Taiwan, where it established the Republic of China led by Chiang Kai-Shek. In the 1950s, members of groups persecuted in Mainland China as xie jiao, including the most targeted movement in that decade, Yiguandao, escaped in significant numbers to Taiwan, although they knew the Kuomintang was also hostile to them.

During the Martial Law period, i.e., between 1949 and 1987, Yiguandao was indeed subject to surveillance and periodical crackdowns in Taiwan. It was also falsely accused of practicing black magic. Other movements subjected to crackdowns in the martial law period were those whose headquarters were in Japan, including Tenrikyo and Soka Gakkai, as the memory of fighting the Japanese was very much alive in the Kuomintang elite.

It should be remembered that Chiang Kai-Shek himself had converted to Christianity, and saw American-style Protestant Christianity as both a modernizing and an anti-Communist force. However, this applied to mainline Christianity only. Non-mainline Christian new religious movements were easily accused of being xie jiao. As Professor Tsai evidenced in a recent article, in 1974 a violent crackdown targeted The New Testament Church, a Pentecostal movement founded by Christian Hong Kong movie star Mui Yee, whose headquarters had been moved after the founder’s death in 1966 to Mount Zion, near Kaohsiung, in Taiwan.

After the Mount Zion community had been disbanded by the 1974 crackdown, a second and equally violent raid, where devotees were badly beaten and some died, targeted members of The New Testament Church around Taiwan in 1985. Only protests by American Pentecostals and the intervention of the U.S. government ended the persecution.

The Kuomintang had also developed a mutually supporting relationship with BAROC, the Buddhist Association of the ROC, allowing the government to claim that notwithstanding the Martial Law it was a friend and patron of religion. However, the authority of BAROC was eroded by independent Buddhist masters and new movements, which often advocated democracy and social justice and were thus at least implicitly critical of the government.

This was one of the reasons leading to a renewed persecution of groups labeled xie jiao in the post-authoritarian phase of Taiwan. Martial law was lifted in 1987, but the Kuomintang largely maintained its power, and only from 2016 has Taiwan had both a President and a majority in the Parliament not affiliated with nor including the Kuomintang.

Taiwanese voters were first allowed to elect their President in 1996. Some leaders of religious movements believed that democracy implied that they were free to express their support for the presidential candidates who opposed the reelection of Kuomintang’s President Lee Teng-Hui. One of these candidates was Chen Lu-An, a disciple of Master Hsing Yun, the abbot of the large Buddhist order Fo Guang Shan. The abbot openly promoted Chen as a presidential candidate, as did Master Wei Jue, the leader of another Buddhist order, Chung Tai Shan.

Eventually, the Kuomintang candidate Lee was reelected, and his Justice Minister Liao Zheng-Hao carried out a purge against the religious movements that had not supported Lee. In addition to Fo Guang Shan and Chung Tai Shan, the crackdown on groups labeled as xie jiao targeted the Taiwan Zen Buddhist Association (later the Shakyamuni Buddhist Foundation), founded by Zen Master Wu Jue Miao-Tian, the menpai (similar to a “school”) of qigong, self-cultivation, and martial arts Tai Ji Men (whose case will be discussed by Professor Chen in this session), and the Sung Chi-Li Miracle Association, a new Taiwanese religion whose founder is Master Sung Chi-Li.

All these movements were accused of being anti-government, of “religious fraud” and tax evasion (importing some rhetoric against “cults” from the West and Japan), and at least by the media also of sinister magical practices (Tai Ji Men was accused, falsely and somewhat ridiculously, of “raising goblins”), thus continuing the traditional rhetoric against the xie jiao.

In the end, long prosecutions led in some cases to sentences for administrative violations (while in the case of Tai Ji Men the defendants were found innocent of all charges), but the main accusations did not hold. Even Master Sung Chi-Li, who had been sentenced to seven years in jail in 1997 and had been depicted as the quintessential “evil cult” leader defrauding his followers of large sums, had his conviction overturned by the Supreme Court in 2003.

We know that not all religious movements respect all the laws. Yet, what happened in Taiwan in 1996, featuring the persecution of groups later declared totally innocent by the highest courts of the country, including Tai Ji Men, is yet another example of the political use of the category of xie jiao. The label was born in the Middle Ages in China to crack down on religious groups perceived as not supporting the power that be, and has continued to be used for this purpose ever since.

source: Bitter Winter Magazine