The 7th-century Japanese ruler taught that law and its enforcement cannot be independent from conscience.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the webinar “A Real, Independent Justice for Tai Ji Men” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on January 11, 2023, Taiwan’s Judicial Day.

Today we commemorate an important date for Taiwan, January 11, 1943, when the Republic of China (R.O.C.) entered into a new treaty with the United States and the United Kingdom, making R.O.C.’s judicial system completely independent from any foreign jurisdiction.

Independence is a key element of any legal jurisdiction. As long as it is dependent from other countries, a legal system is not fully established. In Europe and elsewhere, countries have decided that a portion of their independence may be surrendered to supra-national jurisdictions such as the European Court of Justice, the European Court of Human Rights, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, but they did it voluntarily and in an endeavor to reinforce rather than weaken their systems.

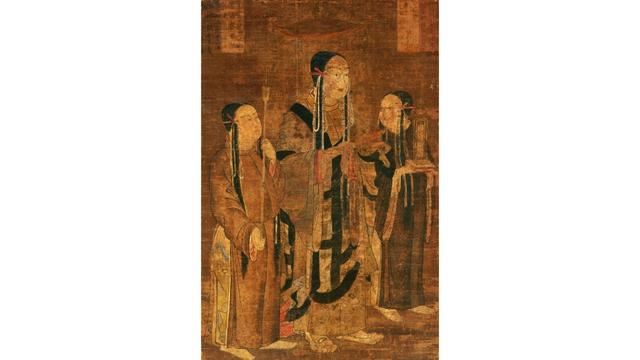

What is, however, independence? This theme was a concern for Prince Shotoku, a beloved figure in Japan whose real or imaginary portrait has been reproduced on countless paintings, statues, and even Japanese banknotes. Shotoku served as regent for his aunt, Empress Suiko, from 593 to 622 CE, and became immensely popular.

There is a scholarly controversy in Japan on whether he wrote a single Constitution for Japan, or five, or six since the authenticity of texts reproducing these documents is much debated. However, for our purposes today, what is important is his notion of the law and the state officers.

Shotoku wrote foundational texts for Japan, and although speaking of independence in the 7th century would be anachronistic, he was evoked in the 19th and 20th centuries as a symbol of Japanese identity. He also asserted the equal dignity of Japan in its dealings with China. We can thus see in his political activity an affirmation of independence.

However, at the same time he insisted that the law and its enforcement cannot be absolutely independent. Although they should not be dependent on foreign powers, they should be dependent on moral values and conscience.

A key point of the texts attributed to Shotoku is that if rulers and bureaucrats believe they are the owners rather than the servants of the law, corruption will follow. Corruption was already a problem in the 7th century, and the Shotoku writings define it as privileging the officials’ private interests over the public ones.

One famous text attributed to Shotoku states that, “To turn away from that which is private, and to set our faces toward what is public—this is the path of a Minister. Now, if a man is influenced by private motives, he will assuredly feel resentments: and if he is influenced by resentful feelings, he will assuredly fail to act harmoniously with others. If he fails to act harmoniously with others, he will assuredly sacrifice the public interest to his private feelings. When resentment arises, it interferes with order, and is subversive of law.”

Said in other words, the legal system should be independent from foreign control, but should be dependent on morality, honesty, decency—and conscience. When those who enforce the law believe they can do it independently of any control by the ethical principles, and by their own conscience, they start confusing the private with the public. Manipulating the public in the interest of the private is the very definition of corruption.

While he is remembered for a vast program of promoting Buddhism in Japan, Shotoku understood that its advise to state ministers and officials was indebted to what he himself called “the way of Confucius.” No doubt many similar texts can be found in the Chinese and Confucian tradition. And wise advise may well be the same in different traditions. It is also appropriate for all times.

The drama described in the text attributed to Shotoku I quoted is what we saw in Taiwan in the Tai Ji Men case. A prosecutor and several tax bureaucrats were “influenced by private motives” and “sacrificed the public interest to their private feelings.” Tragedy followed.

The Shotoku writings also indicate the solution. Although the words he used were different from those of Dr. Hong and Tai Ji Men, in essence he also invited to turn to conscience.

This lesson remains valid today, and is also the key to the solution of the Tai Ji Men case. Those who turned away from conscience and the public good and allowed their small private interest to rule should now turn to conscience and let the real interests of the law, of Taiwan, of humanity prevail. May the Judicial Day inspire thoughts and deeds of wisdom in those who have the power to solve the Tai Ji Men case.

Source: Bitter Winter