Could the harmony reigning among Tai Ji Men dizi be the reason bureaucrats persecute it? The answer may lie in a literary myth.

by Marco Respinti

*A paper presented at the webinar “A Good Environment for Tai Ji Men,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on June 4, 2022, on the eve of the United Nations World Environment Day.

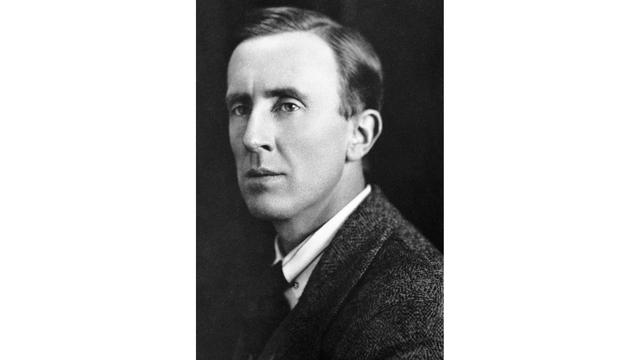

Those who grew up in the West in the second half of the 20th century were familiar with the works of English author J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973) well before his most known books of fiction were popularized by the entertainment industry. Tolkien was a scholar in Anglo-Saxon language, a master in Old Norse literature, a lover of myths, and a talented writer of fairy-tale-like stories, which he always regarded as high sources and vehicles of truth and wisdom.

His masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings (1955–1956), is many works in one. It can be approached from many angles, but I have always considered it also as a gallery of characters, each facing life, death, and fate differently. In this gallery, ranging from high-ranking heroes, kings, and supernatural beings to despicable villains and monstruous bogeymen, a central character, if not the pivotal one, is a humble, simple, plain gardener.

Everyone calls him Sam, but his full name is Samwise Gamgee. He belongs to the fictional people of the Hobbits. Tolkien explains that the meaning of his first name is basically “half-wise.” Does this mean that Hobbits like Sam are stupid? Not at all. Tolkien’s Hobbits are small creatures: in the eyes of the taller ones, they look like children even when they are grown up. Since taller people are universally considered wiser, Hobbits, often called Halflings, seem to be only partially wise. In other words, their simplicity is mistaken for lack of wisdom, while it is truly authenticity, sincerity, and candor.

The simplicity of these Hobbits, which Samwise Gamgee embodies at its best, conveys wit and charity. In Tolkien’s tales, Hobbits are humans understood in their proper relationship with nature and the environment.

A noble and simple Hobbit of Sam’s stock learns from the earth what is essential to lead the earth. Sam the gardener does not worship wildlife: he tames it, knowing that taming the earth means respecting it, as every good farmer and breeder in real-life world knows. Even hunters know it.

Sam is a gardener—and a gardener dominates nature without tyrannizing it. He takes care of flowers, trees, and fields out of love. He even struggles with nature, but parents do struggle to educate their beloved children. A gardener is in fact a person who brings order where order is both missing and needed.

The mark of the gardener, as he who brings order in the wild, is also at work with cattle, flocks, and corrals, where shepherds bring order to an otherwise brutal animal realm. Many of Tolkien’s important characters are trees or masters of trees. The most famous is Treebeard, a tree-giant belonging to the fictional race of the Ents and the oldest living creature that, in Tolkien’s novels, still walks beneath the Sun upon his fictional Middle-earth.

But Treebeard is not a common tree: he is a shepherd of trees and the chief of his kind. He shepherds both animals and plants, and brings order in a forest otherwise savage and ferocious. Again, I suspect that this has a deep relationship with the Christian images of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, Peter as the keeper of the Lord’s sheep, and the pastoral staff as the symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot.

Let me now take more advantage of your wisdom as tall humans, and add another element from Roman Catholicism, not at all out of any parochial or denominational hybris, but because of its universal value.

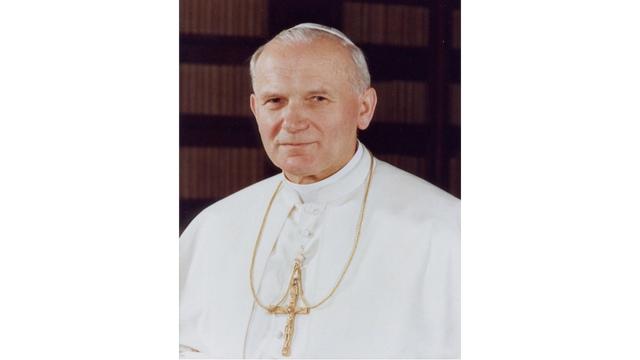

In 1984, Pope John Paul II (1920–2005), now a canonized saint for the Roman Catholic Church, released one of the most important document of the contemporary Pontifical magisterium, the post-synodal apostolic exhortation Reconciliatio et Paenitentia (“Reconciliation and Penance”). Humanity lives in a sea of troubles, he wrote, because the order of things has been broken by human’s fault at the beginning of human history. Human beings need to repent if they want to recover what was broken. The order of creation broke along the four relationships that constitute human environment as a whole: the humans’ relationship with God, with nature, with each other, and with themselves.

Each broken relationship ignites, causes, and contains the following one. If human beings want to reconcile themselves with themselves, with others, and with nature, they need first to reconcile themselves with God. In turn, only reconciliation with God brings about reconciliation of human beings with themselves, with others and with nature.

This is a human ecology and a humane ecology: a common house and environment where human beings may live free, in peace, with mutual understanding, in sight of eternal life on the other side of Heaven.

What does then “A Good Environment for Tai Ji Men” mean? It means that Tai Ji Men Shifu and dizi deserve a habitat where they can enjoy freedom, peace, and prosperity. It is of course Tai Ji Men’s responsibility to envision, build, and bring about such a livable place, but it is also the duty of all other human beings to let them do it freely.

All have the right to be free, and to be let alone. Tai Ji Men must be liberated of all pressures and persecutions to be able to contribute to the human environment and to a humane society.

Members of the Tai Ji Men movement cannot enjoy their inherent fundamental rights as human beings if a healthy human ecology is not provided. As mentioned earlier, a good environment for human beings comes only if humans’ relationship with God, a Supreme Entity or a higher spiritual force, with nature, with each other, and with themselves. If one of this relationship is broken, the order is subverted. If corrupt bureaucrats break these relationships for Tai Ji Men, all the surrounding environment suffers.

This is paradoxical, because Tai Ji Men dizi may be considered a model of citizens working for a good environment. Their whole understanding of life is built upon the tenets of a sincere relation among humans, peace, love, conscience, and respect. I am astonished by the fact that such a pacific community has been and continues to be hit in such a harsh way. And I am beginning to suspect that perhaps the harmony reigning among Tai Ji Men dizi is disturbing for those motivated by greed, power, and envy.

Tai Ji Men may serve as a universal model of a holistic approach to society and nature. Its encompassing dialogue between humans and nature is a key element to rebuke both the claims of radical environmentalism, which considers the human being as a lethal virus, and the materialistic will of power of those who want to control and subdue others, the type of person or bureaucrat that Tolkien’s Treebeard despises as “a mind like metal and wheels.”

The contribution to a human environment as the natural common household for the human family that Tai Ji Men can provide these days is that of Sam the gardener: mere naiveté for those whose arrogance looms large, but truly authenticity, sincerity, and even candor for those who understand true love and peace.

After the Great War of the Ring, when the Dark Lord Sauron was defeated with much pain and deep suffering and many losses, in the year 1427 of the Shire Reckoning, the calendar in use in Tolkien’s Hobbits territory, Samwise Gamgee was elected Mayor of the Shire for the first of seven consecutive seven-year terms. His descendants took the surname “Gardener” in his honor. “Gardeners” may also be the surname of Tai Ji Men, as they are the builders of a truly human and humane environment.

Source: Bitter Winter