12/13/2021. BHANTE DHARMAPALA

Taxes are a typical feature of the state. When the state excessively expands its activities, problems occur, as the Tai Ji Men case demonstrates.

by Bhante Dharmapala*

*A paper presented at the webinar “Administrative Slavery vs. Religious Freedom: The Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on December 2, 2021, International Day for the Abolition of Slavery.

I have two hats, one as a scholar of philosophy and one as a Buddhist monk. What I am not is a legal expert, and I do not feel qualified to comment on the legal sides of the Tai Ji Men case. What I would like to contribute here is a project for a possible, perhaps future, philosophy of taxes, starting from some notes taken from history and anthropology. I think that these notes may also shed some light on the Tai Ji Men case, which moved me deeply and to which I will return at the end of my text.

What we commonly take for granted, i.e., the duty of each citizen to contribute to the organization of society through the payment of taxes, at a closer look calls into question important nodes in the human history.

It is quite evident that the notion of taxation was completely unknown in the small pre-state systems. In that case, there was a communal economy, to which all members of the community contributed directly, benefiting at the same time from the resources that the system made available to them.

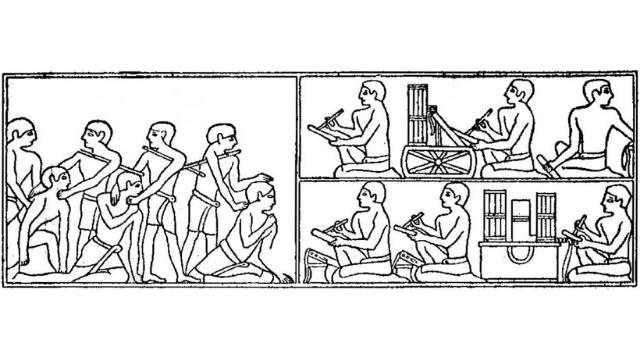

Things changed with the formation of large social groups as a result of the agricultural revolution, when a hitherto unknown entity appeared, which we call the state. It was a part of the social system that was formed in an autonomous form and came to prevail on the rest of the society, dominating it and at the same time providing new services that promoted a reorganization of social relations and life in general.

At the center of this entity we find first of all a core that we could define as ideological, which provides the sense of collective identity as a system of beliefs and practices, through which individuals recognize themselves as part of something ideal that pervades their existence and is transmitted from generation to generation. It is not difficult to see that this is essentially constituted by religion, which is an organized complex of symbols, myths and rituals that provides the glue keeping collective life together.

Next to this we then find another core, material force, which takes charge of internal unity and stability and protection against external threats. Although the former principle, the religious or spiritual one, generally enjoys superior prestige, it is this second core which is decisive in social organizations. As Marx said, the state is the monopoly of force considered legitimate.

If, in everyday life, an individual kills another human being, this is generally punished; but the state can prescribe it on a large scale, sending part of the population to war. Similarly, those who seize a part of someone else’s property are accused of theft, robbery, or extortion; but, if it is the state that does it, it is regarded as a legitimate operation, and is called taxation.

In modern times, the state has gradually taken on different functions, which enter more and more deeply into the lives of individuals: for example, it has entered the fields of education, health care, and social assistance. One might think, however, that these functions are not part of the deep core of the state, since the latter could very well, and profitably, leave them to others. The state can also invade the field of religion, which in a modern secular view should be completely free and separate from the state.

There are, however, two functions that the state cannot delegate to others: these are the exercise of force—i.e., police and armed forces—and taxation. In other words, in its essential core, the state is inseparable from a structure capable of imposing that its decisions be carried out, whatever the will of those involved, and from a second structure that ensures the procurement of the necessary material resources—again, irrespective of the will of those called upon to contribute to it.

From this derives an inevitable consequence: that the action of the tax authorities will never be welcomed with enthusiasm by those who are subject to it. It will be easily perceived as a subtraction of resources in favor of an apparatus seen as parasitic. This is not entirely true, because the state, since the times of the ancient empires, has also contributed in a decisive way, by building a whole series of infrastructures or even through direct interventions, to creating the conditions for the economic prosperity of society. However, it is clear that these conditions are also a function of the increasing drainage of resources, allowing the state to extend its presence more and more.

Thus we come to the present day, and to those multiple functions for which the state is responsible. The current situation presents further problems. At a time when the state has disproportionately extended its apparatus, perhaps beyond what society can bear, the society, at least in its more enterprising parts, has found a way, through the globalization of the economy, to be less and less subject to taxation. Large corporations avoid taxes by moving easily from one country to another.

The result is a condition in which state systems maintain their grip on certain sectors of economic life, which are increasingly squeezed, but have to a large extent lost control of others, which have acquired a power superior to those systems, to the point of determining their direction. We do not know how things will evolve—whether, for example, those who have acquired such power will lay the foundations of a new state organization at the planetary level and will then agree to be subject to it fiscally.

What is certain is that future destinies will be shaped by various circumstances, including the ability to rethink, perhaps even radically, the ways in which the various components of a society contribute to its sustenance: that is, what, some six thousand years ago, took the form of taxation.

In the meantime, those who raise their voices when the tax systems, often weak with the powerful, becomes strong and abusive with minorities, even spiritual ones, do well. Unable to prevent tax avoidance by large corporations, tax bureaucrats become arrogant when dealing with those they perceive as weak. This seems to me to be the case with Tai Ji Men, which became the victim—in the end—of a bullying attitude by tax officers who are weak with the strong and strong with the weak. It is precisely such bullying, against which Tai Ji Men disciples rightly protest, that a philosophy of taxation should help prevent.

source: Bitter Winter