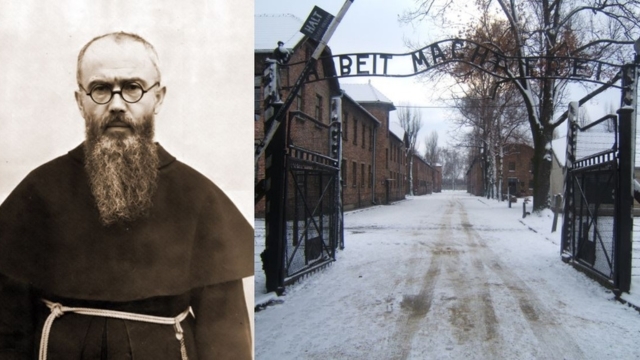

Kolbe is remembered for his heroic death in the Nazi camp of Auschwitz. He was there for his defense of freedom of the press and truth, a lesson also relevant for the Tai Ji Men case.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Introduction to the webinar “Mobilizing the Media for Tai Ji Men and Other FoRB Cases,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on May 8, 2023, after the World Press Freedom Day of May 4.

The United Nations celebrate World Press Freedom Day on May 4. Catholics often connect this date with another, August 14, when they remember the anniversary of the death of the Polish Franciscan Catholic priest Maximilian Maria Kolbe, which was killed by the Nazis in the Auschwitz concentration camp on August 14, 1941.

What this memory has to do with freedom of the press is obfuscated for many by the dramatic circumstances of Kolbe’s death, which are the subject matter of several books and movies. At the end of July 1941, a prisoner managed to escape from Auschwitz. In retaliation, the Nazis ordered ten inmates selected by chance to be closed in an underground bunker and starved to death there. One of the unfortunate inmates selected to die was a Polish military man called Franciszek Gajowniczek. He started crying for his wife and children. Then Father Kolbe stood up and proposed to the Nazis, who accepted, to go to the bunker instead of Gajowniczek. Eventually, Kolbe was taken to the bunker, where he led the other victims to sing, pray, and wait for death calmly. He was still alive after two weeks, and the Nazis decided to kill him with a lethal injection. The prisoner he had replaced, Gajowniczek, survived Auschwitz and led a long a happy life, dying in 1995 at age 93.

This story is so extraordinary that many do not even ask the question why exactly Father Kolbe was in Auschwitz. There were tens of thousands of priests and members of Catholic religious orders in Poland. The Nazis did not exactly like them, but in their majority they were not arrested.

Kolbe was, though, because he was an immensely popular journalist, who edited a daily newspaper, a magazine, and operated a radio station. Hundreds of thousands of Poles followed him every day, and his magazine was simultaneously published in Japanese in Nagasaki. While Kolbe tried to be careful, his readers clearly understood he was critical of the Nazi regime and its crimes. His criticism became increasingly open, until he was arrested in February 1941 and taken to Auschwitz the following May.

Kolbe, thus, was arrested and died because he defended freedom of the press even under the most difficult circumstances. Other journalists who accepted to twist the truth to suit the Nazis survived. They saved their lives but lost their dignity and honor.

Clearly, the story of the Tai Ji Men case does not involve torture and assassination. It is, however, also a story where many journalists unfortunately accepted to publish the calumnies and slander fabricated by the prosecutor who had started the case, creating immense pain and suffering among the Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) and prostituting the freedom of the press and the dignity of journalism.

Basically, they accepted to ignore the truth and propagate lies. Before we hear in this webinar more about the media, freedom of religion or belief, and the Tai Ji Men case, I suggest we meditate on the constitutive relationship between press freedom and truth, by reading some sentences from the last article Father Kolbe was able to publish in his magazine in December 1940, before he was arrested. The title of the article was “Nobody in the World Can Change the Truth.”

“No one can change the truth, Kolbe wrote. The truth is unique. We know this well, yet in our daily life we sometimes behave as if to the same question the answers no and yes could both be the truth… It is true, for example, that right now I am writing these words and that you, dear reader, are reading them. On the face of it, the opposite statement, namely, that I have never written these things, or that you are not reading them, cannot be true. In fact, on this subject, yes and no cannot both be true… If someone wanted to disprove it, and asserted that neither I wrote this text nor you are reading it, the truth would not change, and the one who would deny it would be mistaken or deceived. And even if such deniers were numerous, the strength of truth would not suffer at all. Indeed, even if all the human beings on earth affirmed, published, and swore that I did not write these lines, and that you are not reading them, all this would not be enough to break even a crumb of the granite of truth, namely, that I wrote this text and that you are reading it. Note that not even God can change or erase the truth by a miracle, because He is precisely the Truth by essence. How great is the power of Truth! A truly infinite, divine power.”

Ultimately, the persecutors could kill Kolbe but could not change the truth. This is also true for the Tai Ji Men case. The persecutors could detain the Shifu and others and harass the dizi, but could not change their falsehoods into truths.

A free press is a press capable of recognizing that its real freedom comes from its commitment to the truth. We need media brave enough to tell the truth even when this truth is unpopular, or disturbs the powers that be, as it often happens when religious or spiritual minorities are persecuted. This includes the truth about the Tai Ji Men case.

Source: Bitter Winter