Prosecutors who attacked groups stigmatized as “cults” and slandered them through the media have been active in several countries. Their wrongdoings need to be exposed.

by Maria Vardé*

* A paper presented at the webinar “International Cooperation for Freedom of Religion or Belief and the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on April 24, 2023, International Day of Multilateralism and Diplomacy.

As an anthropologist studying religious and spiritual discrimination in Argentina, the Tai Ji Men case is one of high relevance for me. From everything I learned about the case, I find it strikingly familiar with what has been happening in other countries in the last decades, where the law is used by governments and anti-cult activists in a twisted manner to criminalize, control and neutralize ideological minorities, with a strong reliance on the press and its power to manipulate the public opinion. By striking first in the media with false but sensitive information, the public is frightened and led to condemn the groups that are being accused before knowing anything about them. This mechanism allows further violence, and legitimize illegal actions against the targeted groups. Furthermore, in some cases, these actions permit to pass bills to control and decide what beliefs will be considered more tolerable than others. The most alarming outcome of it all is the systematic violation of human rights.

This malicious use of the media by the prosecutor who started the Tai Ji Men case, which caused considerable suffering to the disciples of the movement, finds parallels also in Argentina.

A decade ago, following the enactment of an anti-cult law in the province of Córdoba, a new and energized anti-cult movement started manifesting itself in Argentina. It has been fueled in recent years by the cooperation of anti-cult activists and a Special Prosecutor’s Office under the flag of the national law against human trafficking. The cooperation works in this way: anti-cult activists, apostate ex-members, and dissident relatives of religious groups devotees file complaints of human trafficking for labor and/or sexual exploitation against the religious minorities. Then, the Special Prosecutor’s office takes the case in its hands and starts a preliminary investigation, often ignoring the facts that contradict the accusation. The argument used to accuse religious groups of sexual or labor exploitation in the absence of physical coercion, forced isolation, or life threats, is that they practice coercive persuasion on their victims (which is nothing more than another name for brainwashing).

When I learned about the absurd accusation of raising goblins in the Tai Ji Men case, I had an immediate impression of déjà vu. There was a clear use of arguments based on imaginary elements of a magical nature, which should remain outside of court cases. In cases in Argentina, group stigmatized as “cults” were also falsely accused of practicing “black magic” rituals. We can also say that brainwashing is a modern name for black magic. Even if coercive persuasion is not a valid argument under Argentine law, the Special Prosecutor’s Office resorts to it in order to explain why the alleged victims of the so called coercive organizations deny being victims. And the office needs to stick to this argument given that, according to its records, 98% of the female victims supposedly rescued by them claim not to be victims. If we take into account that the office also has to deal with real cases of human trafficking, the 2% of real victims gives us an idea of how many cases are real and how many are fabricated. And there is a reason for this: that Special Prosecutor’s office gets a bigger budget and more power as it prosecutes more people. As a result, they no longer seek evidence of physical coercion, nor do they need real victims of the groups they wish to attack. They have also increasingly extended their activities from organized crime to spiritual movements stigmatized by their opponents as “cults.”

In addition to the use of similar imaginary elements, I have found other similarities between the Tai Ji Men case and that of the spiritual and religious minorities recently accused in Argentina. The most noteworthy are the spectacular and violent raids, the anticipated detention and indictment of leaders and members, and the media coverage to publicize the actions of the prosecutors. This is a modus operandi that is increasingly popular and on the rise in various countries. It perfectly describes what happened to Tai Ji Men in 1996.

This model has been repeated in several cases in Argentina, maybe the most famous being that of the Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS), a group of Raja Yoga students. On August 12, 2022, during a quiet philosophy class attended by about sixty people, all adults and on average sixty years old, a spectacular police raid broke into the school classroom and the houses and businesses of fifty other students, several of them located in the same building. The police officers entered breaking the doors and pointing guns to the students. Then, in spite of being offered the keys to the apartments, the police broke every single entrance with rams. The inhabitants of the apartments said that police were clearly looking for money and personal devices, and so it is indicated in the search reports. As it is evident in the photos and videos taken by the students, the police advanced by breaking furniture and throwing everything on the floor. No person was found in captivity or under any kind of exploitation.

After the raids, most of the people raided reported that they had been robbed by the police, who took away jewelry and other items like cameras, printers, and even hair clippers without mentioning them in the search records. While the students were being held in the building for hours without being told what was going on, the media appeared to have a lot of information: for some reason, there were many reporters and cameramen filming the initial police entrance as well as the exit of the first students. They heard the reporters saying “Record that! Here come the prostitutes!” But what the reporters saw, rather disappointedly, was a group of elderly people being assisted by medical personnel due to blood pressure spikes suffered as a result of the violent situation. More than eight months later, those who were present in the raid are still afraid, suffer from posttraumatic syndrome, and some of them had to be treated for severe coronary conditions, which started that day. Before performing any forensic examination of the alleged victims and even before reviewing the elements seized in the raids (mostly money, jewelry, and personal belongings), nineteen students and teachers of BAYS were detained between August 12 and 13, and their assets were frozen. Those that were above the maximum age at which a person can be detained according to the Argentine law were sent to house imprisonment, but only after more than two weeks, which seriously affected their health. The rest were held for three months in miserable, violent, conditions and without the needed medication for severe illnesses like diabetes and high blood pressure. Once again, all this is reminiscent of the detention of Dr. Hong in the Tai Ji Men case.

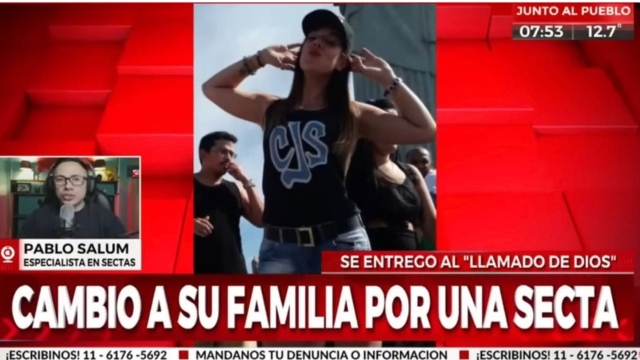

Nearly all the media reports of the Buenos Aires raid and the subsequent events referred to the Yoga School as the “cult of horror,” or some other variation with the word “cult”. They told stories of a horrifying cult that made his followers submit by means of deception, mental control, and punishment, in order to sexually exploit them and deprive them of all their possessions, as well as being guilty of drug trafficking and illegally practicing medicine. Television programs and newspapers published photos and names of the members of the school and conveniently trimmed excerpts from telephone conversations and personal diaries, expressing strange conclusions and biased opinions. Moreover, reporters stood in front of the building for weeks, disturbing the students with insidious questions on camera. These facts show that prosecutors, in addition to making public statements before evaluating the evidence, leaked partial and biased information to the media to make their case more spectacular. That is, as in the Tai Ji Men case, the prosecutors sought public attention and used the media as propaganda tools for their actions.

The trait most worth noting of the Buenos Aires case is that the nine women that are considered as victims and as prostitutes by the prosecutor have actively requested to stop being treated like that, because they claim they are not prostitutes and have never been hurt or manipulated by anyone in the School. Additionally, there is no evidence of exploitation by means of coercion of any kind. But, according to the prosecutor’s office and their twisted brainwashing argument, despite the fact that it supposedly annihilates the free will, the very proof that brainwashing was at work is that it left no traces. If the victims deny being victims, it is because the brainwashing is working well.

The use of false arguments (some of them plainly absurd) and the abuse of authority in order to take a case outside the bounds of rationality, while using every resource to harm a group, is a common characteristic that can be seen in cases like Tai Ji Men and the Buenos Aires Yoga School, and many others.

As scholarly literature about new religious and spiritual movements shows, this kind of procedures are increasing in number and severity. This is why I find the Tai Ji Men case so meaningful and paradigmatic. With the Supreme Court decision and the illegally detained members being financially compensated, it presents a wonderful and encouraging precedent. But at the same time, because of the tax harassment and its consequences that have continued to this day, it is also an example of the great damage that the illegal actions of governmental officers can produce to the entire judicial system and the society. For this reason, I would like to conclude by stating that the systematic repetition in different societies of the human rights violations that we saw in the Tai Ji Men case urges us to make these incidents more visible and to denounce them internationally.

Source: Bitter Winter