Human beings are made for and of liberty. When they lose it, they need a road to recover it—including in Taiwan.

by Marco Respinti*

*A paper presented as the conclusion of the webinar “Tai Ji Men: The Road to Freedom,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on July 18, 2022, United Nations Nelson Mandela Day.

The phrase “the road to freedom” can be easily misinterpreted. If not properly defined, it can push people to think that, to gain freedom, human beings have to emancipate themselves from an alleged intrinsic condition of servitude, revolting against their very nature in a supreme act of revolution. It may be so only accidentally.

The true meaning of the expression “the road to freedom” should in fact be totally reframed. The purest sense of the phrase “the road of freedom” is that human beings need to re-conquer their original condition because they have lost it, reclaiming and repossessing their nature rather than denying it.

All religions and spiritual traditions, and even modern secular philosophy, as in the case of the Swiss thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), clearly maintain this point. Human beings are created, or born, free. This is their nature: human beings are by nature and definition free persons. This has a lot to do with the infinite dimension of human soul and its call to infinity.

Human beings are by nature and definition free persons who lost their original condition and, while always retaining the immortal sparkle of liberty enshrined and engraved in their soul, fell into captivity. Religions and spiritual traditions address and focus on this point from different angles, all to underline one key element they have in common. Some kind of catastrophic fall dragged humans into a condition far different and far away from humanity’s original liberty to make them slaves. Slaves of sins, passions, desire, temptations, ambitions, selfishness, and materialism.

Religions and spiritual traditions have different ways to describe it, but all agree on the serious, even fatal loss suffered by human beings. Some religious tradition even push the argument so far to seriously doubt that humanity can ever recover and regain its original condition. Nonetheless, all religions and spiritual traditions agree that the only way out from this fallen condition is a divine intervention. Of course, the nature and features of this divine intervention are as different as religions and spiritual traditions are. But this is another key element they all share, and this is what matters.

Even secular philosophy basically agrees with this view, offering its own variant. In the preamble of his Du contrat social: ou principes du droit politique, published in 1762, Rousseau famously wrote “L’homme est né libre et partout il est dans les fers,” “Man [sic] is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau blamed the human beings’ fall on society, that he considered corrupt and evil, calling for a social revolution, but in terms of seeing humanity as fallen from its state of original freedom, his theory was similar to those articulated by religions and spiritual traditions. Indeed, Rousseau’s is just a secularized version of them.

Thus “the road to freedom” is rather a restoration than a revolution. It does not mean to liberate humanity from its alleged evil nature and original condition, but to regain its godly nature and ideal condition overcoming the evil that made humanity deviate.

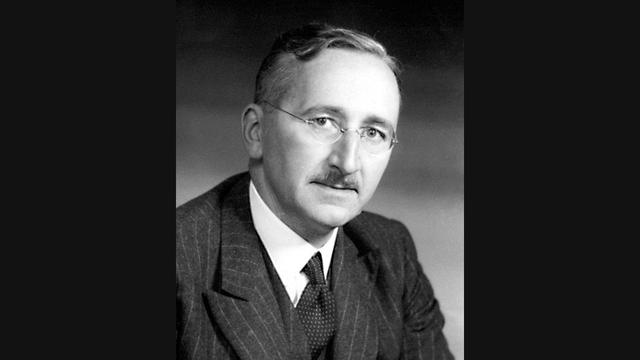

Nobel laureate Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich August von Hayek (1899–1992) reminded us, with his seminal 1944 book, “The Road to Serfdom,” how easily societies can fall, through a number of slippery slopes, including excessive taxation, into tyranny.

Hayek said that the title of his book was inspired by the concept of a “road to servitude” from Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (1805–1859)’s famous “Democracy in America” (1835–1840). Both Tocqueville and Hayek were addressing the very same point I am suggesting here: human beings lost the original liberty they are made for and of, and “the road to freedom” should bring them back—not ahead. In other words, authentic human progress is about retaining rather subverting.

Now, this true human progress has its obstacles. Speakers who discussed the Tai Ji Men case offered perfect description of what the road to freedom truly is: a goal achievable through an uneven and rocky road—as rocky as the road to Dublin, as sings the song of the 19th-century Irish poet D.K. Gavan.

In our webinar, Ida Hsu, a dizi, brought us an important witness. And I want to quote it directly. “I am happy and creative,/ I wonder if other worlds exist,/ I understand that life is not fair,/ But I say that anything is possible,/ I want to have a happy life,/ I hope for the world to be peaceful.” You heard it: it is a poem written by her daughter when she was 10 years old. This is the best description of how liberty and innocence are the original human condition.

Our own road to freedom will continue—for Tai Ji Men and for all those who suffer unjustly, until the restoration of the true condition of free persons for everyone. This struggle will take the shape of a quest for justice in our societies, starting from Taiwan. The Tai Ji Men case shows it perfectly: liberty is the original human condition. Ideology and corruption tried to steal it. We need to recover this original liberty.

Source: Bitter Winter