A well-known Italian novel calls our attention on the problems created when the role of conscience as moral compass is denied.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the webinar “A Question of Conscience: The Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on April 5, 2022, International Day of Conscience.

Since the United Nations, largely thanks to the efforts of Dr. Hong Tao-Tze, the leader of Tai Ji Men, added the International Day of Conscience to their days of observance in 2019, I am considering how this day connects to the fact that what is perhaps the most important Italian novel of the 20th century has the word “conscience” in its title.

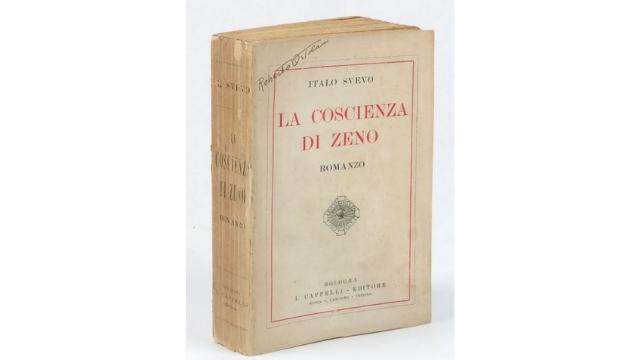

In 1923, Italo Svevo (1861–1928) published “La coscienza di Zeno,” “Zeno’s Conscience.” Svevo’s real name was Aron Hector Schmitz. He was a Jew from the cosmopolitan city of Trieste, which at his birth was part of the Austrian Empire. However, he regarded himself as Italian as evidenced by the choice of “Italo” as the first name in his literary pseudonym.

To understand the novel, one should consider that Svevo’s original mother tongue was German, and he was aware of the ambiguity of the Italian word “coscienza,” which translates both the English “conscience” and “consciousness.” In German, the corresponding words do not resemble each other. “Conscience” is “Gewissen” and “consciousness” is “Bewusstsein.” Interestingly, different editions of Svevo’s novel in German translated the title as “Zenos Gewissen” and “Zenos Bewusstsein.”

The novel is also a match of sort between Svevo and Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) psychoanalysis, a theory by which the novelist was both fascinated and repelled. Freud both established limits for our consciousness (Bewusstsein), claiming that most of what influences us lies behind consciousness, in the unconscious (Unbewusste), and cast suspicion on the conscience (Gewissen), claiming it is not a natural moral compass but simply a repository of the moral theories, which may be highly objectionable, inculcated in each of us by our parents and society.

It is difficult to understand what Svevo really thought about all this, because he used the literary technique of the unreliable narrator. In his literary fiction, the book is edited by an imaginary unscrupulous psychoanalyst who has asked the main character, Zeno, to write down the story of his life and, rather than keeping the text confidential, publishes it as a vengeance against a patient who has interrupted the therapy and is no longer paying him. But he also warns that the text written by Zeno may be full of lies.

What makes the book a masterpiece is that it is both a flow of elements, real or imaginary, that comes to Zeno’s consciousness from the unconscious, very much in the style of Irish novelist James Joyce (1882–1941), who was a great friend of Svevo and had published his “Ulysses” only one year before “Zeno’s Conscience,” and a testament to the fact that Zeno’s conscience fails to work as a moral compass.

Although he achieves, or pretends he has achieved—remember, he may be lying for the benefit of the doctor—, some material success, in fact Zeno acts without a real moral conscience in the four fields the novel is about—health, tobacco addiction, love, and business—and for this reason he fails.

I believe that Dr. Hong, who has made himself heard about conscience all over the world, will be remembered for having rescued conscience from the problems Svevo was immersed in when he published his novel. Conscience had been assaulted not only by Freud, but before him by Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). They all suggested that rather than being something natural or native conscience has been artificially created inside us by social forces not particularly well intentioned.

Svevo’s Zeno, with his complicate relationship with psychoanalysis, is an unforgettable embodiment of the situation of the 20th century humans who have been persuaded by ideologies that they should not listen to conscience. They may believe they are very modern and sophisticated, but in the end they are not able to impose order on the chaos of consciousness and their lives end up in moral bankruptcy.

Dr. Hong told us a simple truth, that we should forget ideologies and come back to conscience as the moral compass. Ideologies, as we know from the tragedies of the 20th century and are experiencing again in the 21st century, by obfuscating conscience create war and destruction. Only those who recognize the central role of conscience can build a civilization of peace and love.

Zeno lives in an era of turmoil, and ultimately does not succeed in recovering his conscience. However, he has his opportunities to understand that, notwithstanding what the psychoanalyst tells him, only conscience can impose the needed order to what is otherwise a chaotic flow of disconnected pieces of consciousness. These opportunities come when he is confronted with suffering and the world’s injustice, although neither he nor the other main characters in the novel profit of them.

There is a lesson in this, and one relevant for the Tai Ji Men case. The modern Western world has somewhat lost the notion of conscience because it has been incapable to answer the question what conscience is. But to define a notion we need to understand its contrary. We know what “hot” means because we also have a notion of “cold.” To understand “conscience” we should have an idea, and an experience, of “lack of conscience.”

Dr. Hong and his dizi had a very painful experience of what the “lack of conscience” is. The lack of conscience of corrupted bureaucrats and officers created the Tai Ji Men case. The great Buddhist sage Nagarjuna (150–250) wrote in his “Treatise on the Great Perfection of Wisdom” that the greatest master is the one capable of “changing poison into medicine.” It is because they experienced the poison of the lack of conscience that Dr. Hong and his dizi were able to administer to the world the medicine of conscience. That we celebrate today the International Day of Conscience proves that the medicine has been effective.

Source: Bitter Winter