11/26/2021MASSIMO INTROVIGNE A+ | A-

Kafka’s novel “The Castle” and Merton’s criticism of bureaucracy describe a situation that is also at work in the Tai Ji Men case.

by Massimo Introvigne*

A paper presented at the webinar “Witnessing for Tolerance: Scholars, NGOs, and the Tai Ji Men Case,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on November 15, 2021, on the eve of the International Day for Tolerance.

During a cold night, a man whose last name starts with the letter K. arrives in a Central European village dominated by a mysterious Castle. He claims to be the new land surveyor, invited there by the Castle.

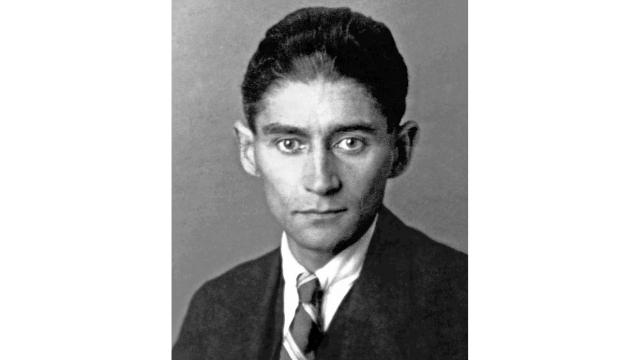

So starts one of the most famous novels of European literature, “The Castle,” that German-speaking Czech novelist Franz Kafka started writing in 1922 and left at his death in 1924 in the unfinished form in which it was published in 1926.

The novel continues with K. meeting the mayor, who informs it that his appointment as the local land surveyor was due to what initially he calls a mistake. But then the mayor corrects himself, explaining to K. that “One of the principles that governs the work of the administration is that the possibility of a mistake must never be contemplated. […] Mistakes are not made, and even if this happened by exception, as in your case, who could say in the end that it was really a mistake?” Besides, K. is told, the question is not whether a bureaucratic decision is reasonable or stupid. If it is properly stamped, it should be obeyed.

Stubborn K. does not accept this answer and decides to stay in the village, where he learns how vast and complex the bureaucratic machinery of the Castle is. Detailed reports are written about everything and sent to high officials, who in most cases do not even read them. For common citizens such as K. accessing the bureaucrats and obtaining meaningful answers is impossible.

The novel is interrupted with K. still struggling to get a response from the bureaucrats. It seems that the end Kafka died before writing should have shown K. dying of exhaustion at the very moment a letter was arriving that might have included an answer from the Castle.

Some have argued that in the novel Kafka was reacting against the praise of bureaucracy by one of the founders of the science of sociology, Max Weber, which had not only been expounded in specialized scholarly works but also in popular articles such as the one Weber wrote in 1917 for the Frankfurter Zeitung. Indeed, we all use the word “bureaucracy” because of Weber, and he believed that bureaucracy was needed for the modernization and rationalization of the state.

Had Kafka read the more specialized works by Weber, he would have found there that bureaucracy also risks becoming a stahlhartes Gehäuse, a German expression that has been translated, perhaps inaccurately, as “iron cage.” If not corrected by politics, bureaucracy may become “as hard as steel,” incapable of flexibility. Interestingly, this degeneration according to Weber was inherent in the bureaucratic system as it had been originally invented, not by politics but by religion through the Puritans.

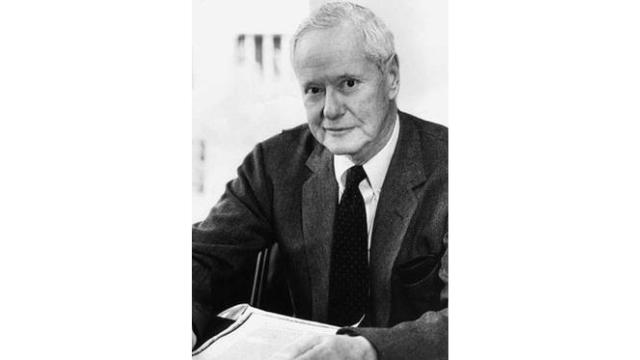

Among later sociologists, it was the American Robert K. Merton who mostly insisted on the degeneration of modern bureaucracy, which he described in 1940 through four passages. First, to be effective bureaucracy should demand a rigid adherence to regulations. Second, bureaucrats lose sight of the fact that regulations are means to achieve ends, and regulations become ends in themselves. Third, bureaucrats refuse to accommodate cases not explicitly covered by the regulations. Fourth, because of this lack of flexibility the effectiveness of bureaucracy turns into injustice and inefficiency.

While we celebrate the International Day for Tolerance, we can also say that bureaucracy becomes a tool for intolerance. The mechanical, impersonal, non-flexible answers, or non-answers, of the bureaucrats may be easily lampooned but they also cause injustice and suffering. Kafka never intended his novel as humorous, and it should have ended in tragedy.

Kafka and Merton may help us read the otherwise ununderstandable answers two Taiwanese ministries, of Finances and of Justice, sent to the Overseas Community Affairs Council, a cabinet-level council of the Executive Yuan of Taiwan, respectively on August 31 and September 10, 2021.

The question raised by the Council was how it had been possible that gifts given by dizi to their master in the year 1992 were taxed as alleged tuition of an alleged cram school, while the same gifts for all the other years Tai Ji Men has been in existence were acknowledged as tax-exempt. It was because of the tax bill for 1992 that in 2020 the Administrative Enforcement Agency tried unsuccessfully to auction and then seized Tai Ji Men’s sacred land.

The National Taxation Bureau and the Administrative Enforcement Agency argued that the difference was that for 1992 there was a decision by the Supreme Administrative Court rendered in 2006, which was final and no longer appealable. However, this decision was rendered before the criminal division of the Supreme Court of Taiwan carefully examined the substance of the matter and clarified in 2007 that Tai Ji Men and Dr. Hong had never evaded taxes. Under the principle that a criminal decision supersedes an administrative court’s decision, the NTB should have revoked the unlawful tax bill based on the Supreme Court’s decision of 2007 right away, and it is a general principle of law that patently unjust decisions may always be rectified.

The Ministries answered that the National Taxation Bureau’s decision to maintain the 1992 tax bill and the Enforcement Agency’s seizure and auction of Tai Ji Men’s land were formally unimpeachable, as they followed the 2006 Supreme Administrative Court decision. Nevertheless, in a 2010 public hearing in the Legislative Yuan, the National Taxation Bureau promised to revoke the enforcement and to end the Tai Ji Men tax case within two months, but they broke the promise afterwards. In 2018, the Supreme Administrative Court even ruled that the decision of 2006 did not consider the criminal decision and the fact that the red envelopes for the shifu (Master) of Tai Ji Men were gifts as validated by the results of a public survey, confirming that the 2006 ruling was a wrong decision. Therefore, it was illegal for the Administrative Enforcement Agency to rely on the 2006 judgment to seize and auction the land of Tai Ji Men.

These are clear examples of the bureaucratic distortion noted by Kafka and Merton. From a substantial point of view, the decisions did not make sense because absolutely nothing different happened in 1992 with respect to the other years. However, just as the mayor told K. in Kafka’s novel, the answer was that by definition the bureaucracy does not make mistakes, and once it is properly stamped a bureaucratic decision may look absurd and stupid but is perfectly valid and should be followed.

It seems that a vicious circle has been created, and there is no exit. As Merton noted, in a democratic state there is only one way to avoid the intolerance of the bureaucracy. Democratically elected politicians should take over and solve the problems. This should be the solution of the Tai Ji Men case.

Source: Bitter Winter